I found Jay Caldwell’s new CGH (Caldwell Gallery Hudson) at 355 Warren fascinating as a veritable museum of fashionable fine art, rich with an eclectic variety of twentieth century American painting (and a smattering of nineteenth) perfectly matched to the tastes of the upper east side of Manhattan.

I do not make this characterization facetiously or even lightly. Priced in the thousands, and hundreds of thousands, Caldwell presents a quality collection of abstract, figurative, and landscape works in an appropriately luxurious gallery setting, though I felt that considering the kind of money we’re talking about here, the metallic carpet and industrial balustrading were incongruous. The refreshments were not, nor for that matter was the crowd at yesterday afternoon’s opening: canapés, chocolates, and champagne were liberally offered to a refreshingly flamboyant invited guest list of connoisseurs who were a picture themselves.

The art, unabashedly bourgeois, is impeccably framed and beautifully hung amidst a smattering of fine furnishings of the period (a Wyeth here, a Grant Wood there, a beautifully lit neoclassical statue, an exquisite mid-century mahogany credenza, an elegant shag rug of overlapping amoebas), so much so that I was inclined to drool at the intelligence of it all without seeing the trees for the forest.

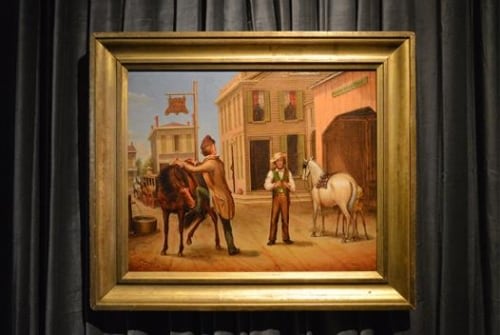

And thus with sheer delight, I came across, tucked away in a far corner of the upstairs gallery, a little gem, from which I could hardly avert my eyes, even if it was the most inexpertly executed painting in the whole show. The American primitive, Otis Bullard’s 1853 “Horse Trade Scene, Cornish Maine” is a roughly two-foot-square tightly cropped panorama of two tradesmen in a New England town square with their rides, under the stern gaze from a second floor window of a matronly figure, surmounting a door upon which is painted a trompe l’oeil of an intriguing inscription. According to the impressively knowledgeable gallerist, the notice refers to another, quite different work by the artist: Bullard’s long-lost but celebrated “moving panorama” of New York, a 3,000-foot-long painting depicting the streets, residents, and sights of lower Manhattan in the 1850s, unveiled as a wildly successful two-hour virtual tourism experience to hundreds of thousands of Americans paying 25 cents a pop in venues across the heartland. (Peter West’s online essay on this curious work is well worth reading at http://www.common-place.org/vol-11/no-04/west/)

All in all, a valuable and fascinating survey that punctuates and enlivens Hudson’s evolving visual arts scene to great effect as a neat transition from Peter Jung’s invaluable sanctuary of nineteenth century American painting to John Davis’s adventures in recent modernism across the street.

By John Isaacs